Letters written and received far from home during wartime have special meaning for people who serve in the armed forces. From the letters on display at the Smithsonian’s Post Office Museum in Washington, D.C., dating from the American Revolution to 2010, to the iconic Sullivan Ballou letter written during the Civil War, featured in the Ken Burns film, The Civil War, produced by PBS, the impact of such letters and their personal and historical significance cannot be overestimated.

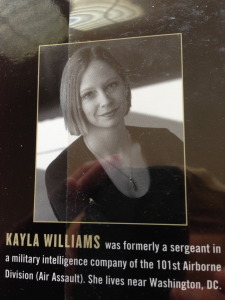

Kayla Williams is of a new generation of women soldiers, who now make up 15 percent of today’s U.S. Military. She served for five years as a translator in Arabic for military intelligence in the U.S. Army, during which time she was deployed for a year to Iraq. Her memoir, about being young and female in the U.S. Army, Love My Rifle More Than You (W.W. Norton, 2005), describes her experiences and the specific challenges facing women in the military.

“My year in Iraq was difficult,” she wrote,” but it would have been nearly impossible for me if it weren’t for all the support I got from people back home. To everyone who wrote me and sent me packages, thank you – I cannot properly express the difference it made to get letters and treats so regularly.”

Recently, Kayla, who lives in Washington, D.C., and I spoke about the role and importance of letters in her life while serving in the military and especially during her service in Iraq.

Kayla describes her letters home as both “candid” and uncensored, but respect for operational security requirements prevented her from being as open in her letters as she could be with her personal journal. It was to the journal that she turned to record her private thoughts and daily challenges while serving in the military, including sexual harassment, misunderstandings among members of her team, and the incompetence of a few of her senior officers.

Mail call is an important day for people serving in the armed forces, especially when serving overseas. Kayla corresponded regularly with both of her parents, as well as with good friends. In a letter dated Sept. 21, 2003, she wrote to her mother, “I think of you as having taught me to answer letters because you always nagged me to do it and to write thank you notes.” She goes on to discuss why Qatar does not have a “u” in it (in Arabic, it is simply QTR) before delving into a more philosophical discussion about the nature of evil, ethics, character and responsibility.

“I wrote lots of letters back and forth to my best friend (“Zoe” in the book), who was also in-theater, and also letters to team members who went home before I did and a few other fellow soldiers. Family members (my parents, a couple of aunts, my brother and one of my sisters) were fairly diligent about exchanging letters with me. My mom’s high school boyfriend, interestingly, was wonderful about writing letters and sending care packages.“

While serving in Northern Iraq, Kayla received some “real packages” containing snacks, novels, magazines, etc. In addition to packages sent by friends and family, “sometimes school or community groups would send care packages and/or letters, which we always appreciated. It was great to feel remembered and recognized.”

“My dad’s mailman,” she noted, “a Vietnam War veteran, collected magazines from everyone on his route and sent them to us – everything from Cat Fancy to Guns & Ammo – and that in particular was extremely touching to me. For a while, it seemed like every community group was being told to send the same thing (sunscreen and baby wipes), so we actually had an overabundance of those things.”

We, as civilians, are sometimes encouraged to send letters or packages to people serving overseas. Kayla’s advice on this: “When I send care packages to friends who are deployed now, I make an effort to send things that I think they may have a tough time finding or that others may not be sending: trail mix with unique flavors, shelf-stable Indian food, miso soup mix, fancy dark chocolate, face lotion, drink mix packets in unusual flavors, stuff like that. I definitely encourage other people to do this, and include things that you may have access to that are locally meaningful (regional foods, for example.) One thing: do not, do not, DO NOT ship food and detergent in the same box. It doesn’t matter how well you try to sub-package things, if you do that, the cookies will always taste like Tide. It’s a downer.”

Late in her deployment, Kayla had more down time. When she worked the night shift, it was “wildly boring.” Her aunt was ”kind enough to send me a cross-stitch so I had something to occupy my hands (and brain). It hangs in my guest room today. :-)”

Sometimes there were surprises in the mail. For instance, Kayla’s ex-husband sent a care package to Iraq that included a bottle of wine. “I don’t know what he was thinking… I had to turn it in since it’s forbidden and it was kind of an issue.” Mail generally was delivered in sequence, but “it was very common to get a big stack at once, possibly including several sent by the same person at different times.”

What, I asked, made some letters more meaningful than others?

“The letters I got from “Zoe” were particularly meaningful … since we were in the same unit and were both best friends and roommates stateside, I was so used to talking to her about everything, and it was hard to lose that once we were deployed. Then eventually I was the only woman at a couple different sites for months on end, and felt lonely and isolated. She was probably the only person I was being completely honest and forthcoming with in letters, telling her things I wouldn’t have told people back home, and hearing back from her with reassurances and validation was tremendously important.”

On the subject of mail and real letters, Kayla is passionate. “I miss them. I almost hate email… I’m not as thoughtful in emails, rarely write long emails, don’t put as much attention into what I’m going to say. I miss both getting and sending letters, the feel of paper and smell of ink. I still send paper cards to people for a lot of occasions – sometimes I feel like I’m single-handedly keeping the USPS in business, since so few young people (am I still allowed to call myself a young person? probably not) send cards or letters. But there’s just something about them, knowing someone took the time and effort, that makes them more special.”

Kayla Williams will be a speaker at the San Francisco Main Library’s Koret Auditorium October 15 at 6 p.m. as part of a panel discussion called Women in War: Truth and Fiction. The discussion, to be moderated by author Evette Davis, is sponsored by Swords to Plowshares and Litquake, in association with San Francisco Public Library. It will feature a panel of women soldiers, including Kayla Williams; Mariette Kalinowski contributor to Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War; and former U.S. Navy Seal Christopher Beck, now living her life truthfully as Kristen Beck, a transgender woman. Come listen as these writers explore honesty in war memoirs, what it means to fight as a female soldier and more.

Resources:

Thank you to Kayla Williams for her generosity and service in the U.S. Army, and for sharing selected letters with me.

The Civil War. Letter by Sullivan Ballou

Love My Rifle More than You by Kayla Williams. W.W. Norton, 2005

PBS. The Civil War. A Film by Ken Burns

Plenty of Time When We Get Home by Kayla Williams. W.W. Norton, 2014

Francine

14 Oct 2014The power of letters! Wish I could attend the SFPL event you mention–too far to travel. As for email, it can be a real letter, too–given a thoughtful writer. Social Correspondence has made that point already.

– Francine – wish you could be here too!