This story of love and separation during the First World War came to me quite by accident. My colleague Jennifer Greenlee and her family have been looking for an archive that could become an appropriate yet accessible permanent home for 140 letters written between 1917 and 1919. The letters, written by her grandfather Joseph Bosque to his sweetheart (and later his wife, Jennifer’s grandmother), Annie Corbett, described his experiences during Army basic training in Jacksonville, Florida and later, from his post in France.

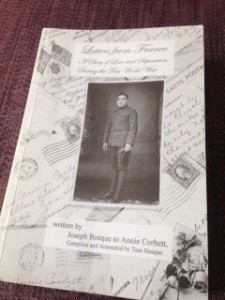

As noted by Jennifer’s late cousin Tom Bosque, who published a compilation of the letters in a limited edition book exclusively for family, the letters are not the history of World War I, but rather, one person’s story, a history. Jennifer’s copy of Tom Bosque’s book, which was en route to the post office to be sent to an archive for consideration, inspired a conversation between us, and resulted in Jennifer allowing me to read it before she mailed it away. I am very grateful that she was willing to share her family history with me.

Joseph Bosque was one of the lucky soldiers, a survivor of a terrible war. He was a San Francisco native, born in the Ocean View district, and joined the U.S. Army in December 1917. He was sent to basic training in Jacksonville, Florida and to France six months later.

Although his position did not require him to engage in active combat, his observations were astute and tell us much about the expressions and time in which he lived. For instance, upon arriving at Camp Johnston in Jacksonville, the soldiers were put to work clearing a field, which became their camp. He noted that thousands of bushes and tree stumps were cleared within hours, leaving everything “clean as a whistle.”

In another letter, he wrote of his wish to visit St. Augustine, “the oldest city in the U.S.,” once he had “the kale.” Apparently, green dollars were necessary, because St. Augustine prices were high. A box of ginger snaps cost ten cents, an orange five cents, and a jar of jelly twenty cents. When he was waiting for information about a new post, it was waiting for “the dope.” He referred to an Army meal as “some feed.”

Joseph was an optimist, who loved food, and mentioned on several occasions about the weight that he was gaining. He always downplayed any hardships or concerns he might have had, constantly reassuring Annie with references to their future together.

Although Joseph did not have a college degree, he was chosen over many others to join a clerical unit, one of only five selected from his unit. Although he attributes this good fortune to his “practical experience,” his family viewed the assignment also as a reward for his excellent penmanship.

Even before being stationed in Europe, Joseph noted in his letters that there are gaps in time when letters were delayed. On January 18, 1918, he wrote to Annie that he received seven letters in the same day. “Can you imagine that?” he wrote. “Two from you, 2 from home, 1 from Dan Ahern, and 1 from Nellie K. It will keep me busy answering them.” Later, he added, “The weather has been dandy here so no complaints are heard.”

In a prescient moment in February, 1918, Joseph said, “It’s surely too bad that California has had such a dry year.” (It did in fact rain sometime shortly after he wrote this letter).

Food continued to be a topic throughout the correspondence, as was his steady faith as a Catholic, which clearly contributed to his mental well-being. He received home-baked cakes and cookies and boxes of chocolates from Annie, but also from “Lucy K.” and other young ladies, who he refers to at times in his letters. Nonetheless, it is always clear that he had eyes only for his Annie, signing his letters with love and sometimes love and kisses from “your Joe.”

Other treats sent through the mail included apples and dates, and even cigars. Self-imposed camp rules among the soldiers dictated that if the food was good, it was to be shared with others. If not so good, one could keep it to oneself. Upon receiving a box of chocolates from a Miss Onyon in April 1918, Joe said to Annie, “Believe me, it feels good to get postals and packages from old time friends as you know you are not forgotten.”

There was always anxiety about what would come next. The soldiers were kept busy with physical drills, and also with classes, teachings that might benefit them at some future time. They were fitted with new clothes and received kits. But it wasn’t until May 1918 that ten soldiers, selected from various clerical units, received orders to report to Camp Merritt in New Jersey, in preparation for overseas duty.

En route by train to New York, the soldiers had a 10-hour layover in Washington, D.C., where they made good use of their time. “The capitol building is a wonderful building,” he said, “but the most wonderful of all is the Congressional Library Building. Words can’t express the beauty of the interior. All marble and tapestries and the lighting system reminded me of the fair. It surely must have cost a mint of money.”

Camp Merritt also included a library, as well as a writing room, a cafeteria and billiard room. “All the books are free to the boys,” wrote Joe, “and they request that the fellows take the books across the seas with them and pass them around.”

The advantages of Camp Merritt were of limited duration. It was sufficient, however, for Joe to visit New York City twice. “Take it from me, it is some town,” he told Annie. In New York, he visited Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and even took in a show. Back at camp, he was given “6 suits underwear, 10 pair sox, 2 Suits, Raincoat, Overcoat, 2 pr. Leggins, 2 pair Gloves (1 woolen and 1 leather), 3 pr Shoes, etc. I guess nobody can say anything about how Uncle Sam treats his boys.”

Military letters were not private. Because he was unable to say when or where he was posted, he left clues in his final letter from Camp Merritt. He signed the letter as “Joseph.” This was the code he had developed, that his use of his full name would be a signal that he was on his way, and might not be able to write again for a while.

With many farewells and good wishes sent to Camp Merritt, within weeks Joe was on his way overseas duty. “With best of love, I will say au revoir, ma chère.”

Until we meet again.

Sources:

Letters from France: A Story of Love and Separation During the First World War, written by Joseph Bosque to Annie Corbett. Compiled and annotated by Tom Bosque.

With special thanks to Jennifer Greenlee and the Bosque family.