High on a shelf in the closet of my parents’ bedroom there was a box full of letters, written from 1942–1944. It was wartime, and my father, a Lieutenant in the U.S. Navy, was stationed in Tiburon, but spent his days on a World War I era minesweeper, the U.S.S. Eider. He was 21 years old in 1942, and my mother was 19. As a teenager, I very much wanted to read the letters, but because I was told not to, I didn’t.

There are two kinds of children, it seems: those who won’t take no for an answer, and others who generally follow the rules. My brother was one of the former. Had he had interest in the letters, I have no doubt that he either would have begged and wheedled until he got to read them, or he would have taken down the box without permission, read them and returned them to their position without anyone’s knowledge. Sometimes to my regret, I fell more into the range of the obedient child, and therefore never got to read the letters. They vanished forever after my mother’s death, 40+ years after their wedding date in 1943.

Speculating on their content, and given their ages at the time, it is highly unlikely that there were any dark secrets to be revealed, official or otherwise – no previous wives or husbands, no “premature” babies, no military secrets. So, why were they so private, and what caused them to become irrevocably lost?

The answer, most likely, is that they were “mushy,” perhaps even racy. Given the lack of social media, the prohibitive cost of phone calls, and inaccessibility to shipboard, people tended to be more candid in their letter writing back in those days. The U.S. Mail is and always has been private – there was no need to worry about an e-mail or text going astray and going viral on the Internet.

Although it turned out that the Golden Gate and the west coast did not suffer attack, San Francisco was fully prepared. Just as the U.S. Army maintained and manned bunkers throughout the Bay Area, the U.S.S. Eider was the watchdog of the Golden Gate. The ship was stationed at the “submarine net gate, where every ship, naval or cargo, must be identified before it can get the necessary clearance to enter or leave port,” according to a July 6, 1944 article in The Oakland Tribune. The article goes on to say that the Eider’s “machinery for opening and closing the gate is almost as large as the Eider itself, but she is also armed and ready for eventualities.”

This is at the heart of what I would have liked to know. What was it like to be young and in love, so near to one another, and yet so far? The uncertainties of life during a war certainly must have heightened the senses and made each moment precious.

My mother’s scrapbook lends some clues. My parents liked to go out, and the scrapbook tells of their favorite destinations. They dined at the Pig’n Whistle, where a filet mignon from the grill cost $1.75 and a broiled salmon steak with lemon parsley butter cost $.70. For lunch, roast stuffed shoulder of spring lamb with currant jelly also would have cost $.70.

They also enjoyed dancing, and the Bal Tabarin, a Timothy Pflueger designed building on Columbus at Chestnut that billed itself as “the aristocrat of San Francisco night clubs,” featuring dining, dancing and entertainment, was a bit pricier. At the Bal Tabarin, a filet mignon cost $4.25, and broiled halibut maitre d’hotel was $3.00. In addition, there was a wine and cocktail list, where bottles were priced by the pint or quart, rather than in liters, featuring champagne by Cliquot and Perinet & Fils. Wines from California’s “renowned wineries” included Cresta Blanca, Korbel, Concannon, De Turk, Beringer, Italian Swiss Colony, Calwa, Roma, Wente, Beaulieu and Scatena Brothers.

Other dancing and cocktail date destinations included the Claremont Hotel, St. Francis Hotel, Shriner’s Circus, Cathay House and the Mark Hopkins, renowned for its view at “The Top of the Mark.”

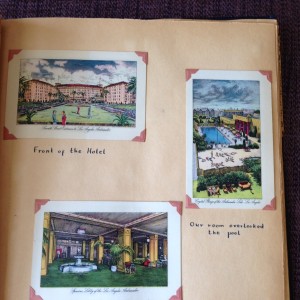

Their wedding, a simple ceremony with three people in attendance, took place at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, but the honeymoon appeared downright posh for the time and circumstances. Postcards from the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles feature a grand exterior, an elegant lobby and a large pool, the Crystal Plunge of the Ambassador Lido. A two-night stay came to $15.69 – a real splurge, plus dancing at the Paladium in Hollywood.

So, there are letters no longer. I don’t know what happened to them, only that some time in the past, they disappeared. I will never know exactly how it felt to be living in downtown San Francisco for a young woman raised on a farm in rural Bellingham, Washington. “You can take the girl out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the girl,” quipped my father’s boss, during the early post-war, civilian years in Berkeley, California. But even without those letters, I know it must have been heady, glorious and exciting.

Sources:

Personal papers of Elisabeth M. Graham

The Argonaut: Journal of the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society, Winter 2006

The Oakland Tribune, July 6, 1944

Cecile

26 Mar 2015What fun! I have a scrapbook/diary that my mother created after a two (2) month trip to the West Coast from Wisconsin in 1950, when I was 14. My father made the cover from a piece of redwood that we acquired in Northern California. In San Francisco we went to the Top of the Mark and I was amazed? horrified? that a “coke” cost $.25. What did I know, being from a small town in southwestern Wisconsin?

15 years ago or so, we learned of a 5 year diary that my grandmother kept from 1928-1932. She and my grandfather lived just a few short blocks from the University of Wisconsin campus in Madison. By that time, my mother and her siblings were all out of the house, so my grandmother rented rooms to college students, mainly men.

My grandmother wrote about the cost of things, particularly fabric, as she sewed a great deal. Like many diaries it offered a slice of life during that time and included many mundane observations.

As it turned out, my mother and her two sisters all married former roomers. The family joke is that if you have marriageable daughters, rent rooms to single men.

Jean Farrington

27 Mar 2015What a wonderful column! I feel your regret at not having actually seen the letters. Recently, I read correspondence from my father, age 18, in the navy to his parents from where he was stationed in the Pacific during WWII and found the thoughts and concerns of this young man fascinating and revealing.